Abstract:

This article attempts to study the flow of political news in tweets of four international news agencies: AP, AFP, Reuters and Xinhua, for 7 years from 2010 to 2016. Theoretically, the study takes its roots from the World System Theory of Immanuel Wallerstein. We used the content analysis method and examined the coverage of political news about 15 world countries (five core countries, five semi-periphery and five periphery countries) in 6746 tweets of international news agencies. We also analyzed the portrayal, retweet rate, favorite rate, and shared portrayal of world system countries. We found that there are significant differences in coverage of political news about the world countries in tweets of international news agencies. Moreover, Traditional hierarchies and structures of political news flow still exist on Twitter. Core countries are covered as well as shared more and positively as compare to the semi-periphery or periphery countries.

Key Words:

Political News Coverage, News Tweets, World System Theory, International News Agencies

Introduction

How are political events of different countries covered and portrayed by international news agencies? This question remains the focus of political communication scholarship. Scholars have studied the different dynamics and patterns of political news coverage in international news flow (Baum & Zhukov, 2019; Corduneanu-Huci & Hamilton, 2018; Hanson, 1998; Meadow, 2009; Paterson, 2003; Taylor, 2003; Westcott, 2008). The political economy approach of global media often criticizes international news agencies for their selective control of global politics (Wasko, Murdock, & Sousa, 2011). They argue that international news agencies are instrumental in determining the importance of global political events, and also they tend to associate international significance with certain political events of world countries at the expense of other events and countries (Atabek, 1996; Boyd-Barrett, 2008; Giffard & Rivenburgh, 2000). Therefore, the present study aims to find the answer about the coverage of political events in international news.

News agencies are the most important organizations in the field of global news. The powers to propagate both the good and evil agenda reside with the international news agencies (Anatsui & Adekanye, 2014). However, they are considered instrumental in their creation and dissemination of news, and they are mostly promoting Western journalism values (Bielsa, 2008). It is argued that international news agencies often portray the Western world view and distort the image of underdeveloped countries (Ambrogi-Yanson, 2010; Bielsa, 2008; Dergisi, 1996; MacGregor, 2013; Ray & Dutta, 2014; Stover & Anawalt, 1983). Furthermore, the analysis of agency output is also relevant here because it is the basis of the majority of international news. The dominant international news agencies are; The Associated Press (AP), Reuters (Jirik, 2013), Agence France Presse (AFP) and recently, Chinese Xinhua also emerged as the dominant news agency of the world (MacGregor, 2013).

Moreover, social media and the internet have changed the journalism trends of information gathering, production and distribution (Griessner, 2012; Kulshmanov & Ishanova, 2014). Now different news organizations are using Twitter for news sharing and production. Even press release organizations are also using Twitter for their textual, audio, video releases. On the other side, international news agencies always remain a key focus of information flow studies (Ambrogi-Yanson, 2010; Bielsa, 2008; Dergisi, 1996; MacGregor, 2013; Ray & Dutta, 2014; Stover & Anawalt, 1983). With the arrival of modern communication and information technologies, their working is also witnessing remarkable changes in information propagation. Furthermore, in this era of digital journalism, Twitter is gaining popularity day by day for news sharing and consumption. Communicative structures of Twitter (tweets, retweets, following, #hashtags, @replies, and actors) also make the Twitter focus of information flow scholars (Alejandro, 2010; Bruns & Stieglitz, 2012; Willis, Fisher, & Lvov, 2015; B. Wu & Shen, 2015; S. Wu, Hofman, Mason, & Watts, 2011). Due to these dynamics and scholarship importance of Twitter, the present study uses Twitter to explore the coverage of political news from the perspective of world-system theory.

World System Theory and International News

An American sociologist Immanuel Maurice Wallerstein is credited for the development of the world-systems approach. Wallerstein (1974) defined a world-system based on the extensive division of labor. He emphasized that there is inequality among the different countries of the world due to the extensive division of labor. He then categorized nations into three categories. 1) core-states: the states where national culture joined the creation of strong state machinery. These states have a strong economy and Cultural status, and autonomy in the world. 2) peripheral-states: the states where the indigenous state is weak. These states vary from their nonexistence, like a colonial situation, to one having a low degree of autonomy like a neo-colonial situation. 3) Semi-peripheral areas stands between the periphery and core states in different dimensions, such as cultural integrity, state machinery strength and complexity of economic activities, etc.

The basic assumption of Wallerstein world system classification is the division of labor. This division of labor further defines the relations and forces of world economic production as a whole. According to Sorinel (2010), all countries of the world can be placed into Wallerstein four categories of core, semi-periphery, periphery and external. Core and periphery categories are most important in these four categories. These are culturally and geographically different. Core regions focused on labor-intensive, and the periphery region on capital-intensive production. The relationship between these two regions is structural. On the other hand, semi-peripheral states act as a mediator between periphery and core. These regions have mix kinds of institutions and activities that exist on core-periphery.

Similarly, Robinson (2007) also elaborated that World System Theory is the production of a capitalist world system, in which the world has divided into three major regions, which based on geographical or hierarchal organized units. The first one is core or highly developed regions of the world. Initially, it comprised of Western Europe and later on, it expanded to include Japan and North America. The second one is the periphery. It comprised of those countries that have been subordinated by force to the core, either its colonialism or other dependencies. It is expanded to include Africa, Latin America, Asia, Eastern Europe and the Middle East. The third one is the semi-periphery, which include those countries or nations that were formerly in the core and are moving down towards the periphery or that were formerly in the periphery and are moving up towards the core. It is argued that values flow from core to semi-periphery, then from semi-periphery to the core. In this way, each category plays a significant role in the international division of labor that replicates this fundamental structure of exploitation and inequality.

According to the Smith and White (1992) fundamental claim of world-system analysis is that international roles, connections and relationships are central independent variables in any pivotal analysis asserting to describe numerous dimensions of growth and development within countries. The world system theory remains the focus of sociological studies (Babones, 2005; el-Ojeili, 2015; Simon, 2011; Sorinel, 2010; Wallerstein, 1974, 2004) and international communication (Blondheim, Segev, & Cabrera, 2015; Chang, 1998; Eijaz & Ahmad, 2011; Golan, 2008; Golan & Himelboim, 2016; Gunaratne, 2001; Guo & Vargo, 2017; Koh, 2012; Letukas & Barnshaw, 2008; Louw, 2009; Wanta & Mikusova, 2010). The present study also focuses on the coverage of political news in tweets of international news agencies. We study the coverage, sharing and portrayal in political news coverage of core, semi-periphery and periphery countries in the tweets of international news agencies according to the classification by Babones (2005) and Chase-Dunn et al. (2000).

Keeping in view the theoretical perspective of world-system theory and international coverage of political news, the following statements are being hypothesized.

H1: There would be significant differences in coverage of political news about Core, Semi-periphery and Periphery countries in tweets of international news agencies.

H2: There would be significant differences in the portrayal of political news about Core, Semi-periphery and Periphery countries in tweets of international news agencies.

H3: There would be significant differences in the sharing of political news about Core, Semi-periphery and Periphery countries in tweets of international news agencies.

H4: There would be significant differences in the shared portrayal of political news about Core, Semi-periphery and Periphery countries in tweets of international news agencies.

Methods

We used the content analysis method to study the coverage of political news about the core, periphery and semi-periphery countries. The universe of this study is tweets of AP, AFP, Reuters and Xinhua from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2016, about world countries. Further, the sample was drawn from world countries and news tweets purposively. Core, periphery and semi-periphery countries were selected on the theoretical foundations of world-system analysis. Firstly, a pilot study of the randomly selected the year 2011 from 2010-16 was conducted to find out the mentions of world countries in tweets of sample international news agencies. Then most mentioned five core countries, five semi-periphery and five periphery countries were selected as sample. We selected 15 countries and categorized them into core, semi-periphery and periphery on the base of previous world system studies (Babones, 2005; Chase-Dunn, Kawano, & Brewer, 2000; H. D. Wu, Groshek, & Elasmar, 2016).

Secondly, to select a sample, Twitter accounts of four international news agencies; the Associated Press (AP) of the United States, Reuters of Britain, Agence France Presse (AFP) of France and Xinhua of China were selected. These news agencies were selected because they completely dominate the international news industry (MacGregor, 2013; Stover & Anawalt, 1983). Furthermore, it is argued that both a short message (tweet) and social interaction (retweet) among users puts Twitter ahead of other sources of news. Therefore, news accounts on Twitter can have more power than traditional news media (Alejandro, 2010). That’s why several communication research studies on social media are taking Twitter accounts of news organization as sample (Armstrong & Gao, 2010; Griessner, 2012; Lotan, Gaffney, & Meyer, 2011; Lotan, Graeff, Ananny, Gaffney, & Pearce, 2011; Willis et al., 2015; B. Wu & Shen, 2015; Yao, Chang, & Campbell, 2015). The tweets were coded for a period of 7 years (from Jan 01, 2010, to Dec 31, 2016). Unit of analysis was the news tweet mentioning the name of any sample country.

Unit of Analysis

Unit of analysis for this study was defined as a tweet of AP, AFP, Reuters and Xinhua, mentioning any sample countries; United States, Libya, Japan, Egypt, China, Iran, United Kingdom, Syrian Arab Republic, Israel, Pakistan, South Korea, Russian Federation, Afghanistan, India, and Turkey. Only English language tweets were coded. Moreover, the only text of the tweets was coded. Images and hyperlinks were not coded nor followed. Only the tweet by the selected accounts was coded. @Replies to the selected tweets were also excluded.

Political News Coverage

Political news in international media is a key focus of political communication scholarship (Baum & Zhukov, 2019; Corduneanu-Huci & Hamilton, 2018; Hanson, 1998; Meadow, 2009; Paterson, 2003; Taylor, 2003; Westcott, 2008). News related to political events, developments and activities of a country has been operationalized as political news for this study. In this study, we coded tweets related to civil-military conflicts, military coups, strikes, protests, civil unrest, processions, elections, political rallies, laws, legislation, bills, political leadership, electoral frauds, rigging, political instability, etc. It was coded as positive if the tweet makes a positive perception of the sample country with reference to democracy & political situation. Conversely, if it makes a negative perception of the sample country, then it was coded as negative in a dyad with the sample country. If it neither makes a positive nor negative perception about the sample country, then it was coded as neutral.

Portrayal @Replies, Retweets and Shared Portrayal

The three categories of portrayal are defined as: Positive, if a tweet creates a positive image of the mentioned country on human perception; neutral, if a tweet creates a neither positive nor negative image of the mentioned country/nation on human perception and negative if a tweet creates a negative image of the mentioned country on human perception. For making grouped level, ordinal data, positive was assigned code +1, and neutral was assigned 0 and negative was assigned -1 code. Hence, the portrayal of the tweet is operationalized as the portrayal of the country.

Replies and comments to the tweets is an important feature of Twitter, which allows Twitter users to comment and give feedback about the specific tweets. In this study, only the replay rate was measured by counting the number of replies to the coded tweet. It does not include the text, graphics, images, or links of @Replies. In Twitter, the most important information spreading feature is retweeting, and news media are the most important information sources due to a large number of followers (B. Wu & Shen, 2015). Therefore, mass media sources play a central role in reaching a large number of audience in any major issue or topics (Cha, Benevenuto, Haddadi, & Gummadi, 2012). The one unique feature of this study is the measurement of retweet rate about the world system countries. Retweet rate determines the information flow and portrayal flow about the countries in the digital world of Twitter. This study only measures the number of retweets of the coded tweet. It does not include the text or quote of retweets. Favorites is another important feature of Twitter. It enables scholars to measure the likeness of countries and issues by Twitter users. Favorite rate was measured by counting the number of favorites that a coded tweet received about the specific countries and issues and a combination of both.

As it is noted that retweet amplifies the message of international news agencies. Here, in this study, it is argued that if a country is tweeted positively by international news agencies and further it is retweeted more by the followers of these agencies, then the collective impact and shared portrayal of the tweet will also increase in a positive direction. However, if a country is tweeted negatively by an international news agency, and it is more retweeted and favourited by its followers, then it will create a negative shared portrayal of that country. So, we developed a formula to measure shared portrayal as follows.

Shared portrayal = portrayal x (Number of Replies + Number of Retweets + number of favorites)

Here portrayal denotes the portrayal of the country, which is valued as +1, 0, and -1. The shared portrayal was calculated by using SPSS and putting variables into the above-defined formula.

Coding

Three coders were selected to code the content. These coders were graduated in Mass Communication & Media Studies & their medium of instruction was English. They were provided three weeks of training about the codebook and coding instructions. Intercoder reliability was obtained 0.82 by Cohen Kappa. Furthermore, the validity of the coding sheet was ensured through expert opinion. Moreover, data from secondary sources was obtained about the countries for seven years, 2010-2016.

Findings and Discussion

This study attempts to study the coverage of political news in tweets of international news agencies about world system countries. We used SPSS and UCInet software to study, analyze and present data. Our findings show that core countries are covered more in tweets of international news agencies as compare to the semi-periphery and peripheral countries (Table 1). However, Table 1 further indicates that there are significant differences in frequencies of political news coverage of four news agencies. AFP and Xinhua cover political news of semi-periphery countries more as compare to the core and periphery countries. On the other hand, AP and Reuter's cover core countries more as compare to the periphery and semi-periphery countries. In this way, findings support us to confirm H1 that there are significant differences in coverage of political news about core, periphery and semi-periphery countries. Our findings contribute in literature of international political news (Baum & Zhukov, 2019; Corduneanu-Huci & Hamilton, 2018; Hanson, 1998; Meadow, 2009; Paterson, 2003; Taylor, 2003; Westcott, 2008). It supports the argument of world-system theory that political news from core countries gained more attention in international coverage of political news (Chang, 1998; Chase-Dunn et al., 2000; el-Ojeili, 2015; Kick, McKinney, McDonald, & Jorgenson, 2011; H. D. Wu, 2000). In this way, we contribute to support world-system theory in the context of the digital news era.

Table 1. Coverage of Political News about Core, Semi-Periphery and Periphery Countries in Tweets of International News Agencies

|

|

News Agency |

Total |

||||

|

AFP |

AP |

Reuters |

Xinhua |

|||

|

World System Category |

Periphery |

428 |

480 |

990 |

19 |

1917 |

|

Semi-periphery |

477 |

200 |

922 |

583 |

2182 |

|

|

Core |

459 |

488 |

1483 |

217 |

2647 |

|

|

Total |

1364 |

1168 |

3395 |

819 |

6746 |

|

X2=827.76,

df=6, p=.01

Literature in

international news and world system theory argue that international news

agencies are instrumental in nature, and mostly they present western or

dominant view of international news (Boyd-Barrett, 2008; Corduneanu-Huci & Hamilton, 2018; Stover & Anawalt, 1983). Moreover, it is argued

that core countries are covered positively, while the other countries are

covered negatively in international news (Chang, 1998; Gunaratne, 2001; Kick

et al., 2011). Our findings also

indicate these differences in coverage of political news in tweets of

international news agencies (Table 2). Table 2 shows that core countries are

portrayed positively in tweets of international news agencies, and on the other

hand, periphery and semi-periphery countries are covered negatively in news

tweets of international news agencies (Table 2). We found significant

differences in the portrayal of core, periphery and semi-periphery countries.

Hence, findings confirm H2. These findings also support the previous literature

and argument off world-system theory (Chang, 1998; Chase-Dunn

et al., 2000; el-Ojeili,

2015; Kick

et al., 2011; H. D.

Wu, 2000).

Further, Table 2 shows that core countries are more liked, retweeted and discussed (commented) as compare to the periphery and semi-periphery countries. We found significant differences in sharing of core, periphery and semi-periphery countries in tweets of international news agencies (Table 2). In this way, our results support the h3 that there are significant differences in sharing of core, periphery and semi-periphery countries. It contributes to world system literature, and our findings imply that not only the international news organizations but also their followers contribute to spreading their pattern of political news coverage. Hence, on the contrary to the argument that new media provides equal opportunities and coverage of political news, we witness the traditional structures and hierarchies of political news on Twitter.

Table 1. Coverage of Political News about Core, Semi-Periphery and Periphery Countries in Tweets of International News Agencies

|

|

News Agency |

Total |

||||

|

AFP |

AP |

Reuters |

Xinhua |

|||

|

World System Category |

Periphery |

428 |

480 |

990 |

19 |

1917 |

|

Semi-periphery |

477 |

200 |

922 |

583 |

2182 |

|

|

Core |

459 |

488 |

1483 |

217 |

2647 |

|

|

Total |

1364 |

1168 |

3395 |

819 |

6746 |

|

X2=827.76,

df=6, p=.01

Literature in

international news and world system theory argue that international news

agencies are instrumental in nature, and mostly they present western or

dominant view of international news (Boyd-Barrett, 2008; Corduneanu-Huci & Hamilton, 2018; Stover & Anawalt, 1983). Moreover, it is argued

that core countries are covered positively, while the other countries are

covered negatively in international news (Chang, 1998; Gunaratne, 2001; Kick

et al., 2011). Our findings also

indicate these differences in coverage of political news in tweets of

international news agencies (Table 2). Table 2 shows that core countries are

portrayed positively in tweets of international news agencies, and on the other

hand, periphery and semi-periphery countries are covered negatively in news

tweets of international news agencies (Table 2). We found significant

differences in the portrayal of core, periphery and semi-periphery countries.

Hence, findings confirm H2. These findings also support the previous literature

and argument off world-system theory (Chang, 1998; Chase-Dunn

et al., 2000; el-Ojeili,

2015; Kick

et al., 2011; H. D.

Wu, 2000).

Further, Table 2 shows that core countries are more liked, retweeted and discussed (commented) as compare to the periphery and semi-periphery countries. We found significant differences in sharing of core, periphery and semi-periphery countries in tweets of international news agencies (Table 2). In this way, our results support the h3 that there are significant differences in sharing of core, periphery and semi-periphery countries. It contributes to world system literature, and our findings imply that not only the international news organizations but also their followers contribute to spreading their pattern of political news coverage. Hence, on the contrary to the argument that new media provides equal opportunities and coverage of political news, we witness the traditional structures and hierarchies of political news on Twitter.

Table 2. Differences in Portrayal, Sharing and Shared Portrayal of Political News about Core, Semi-Periphery and Periphery Countries in Tweets of International News Agencies

|

|

N |

Mean |

SD |

F |

Sig. |

|

|

Portrayal of the Country |

Periphery |

1917 |

-.39 |

.86 |

300.027 |

.000** |

|

Semi-periphery |

2182 |

-.00 |

.95 |

|

|

|

|

Core |

2647 |

.26 |

.87 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

6746 |

-.01 |

.93 |

|

|

|

|

Number of Tweet Replies |

Periphery |

1917 |

4.57 |

11.18 |

37.690 |

.000** |

|

Semi-periphery |

2182 |

5.54 |

11.07 |

|

|

|

|

Core |

2647 |

7.91 |

16.58 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

6746 |

6.20 |

13.60 |

|

|

|

|

Number of Retweets |

Periphery |

1917 |

87.94 |

108.29 |

6.428 |

.002** |

|

Semi-periphery |

2182 |

89.75 |

139.64 |

|

|

|

|

Core |

2647 |

99.94 |

122.21 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

6746 |

93.23 |

124.59 |

|

|

|

|

Number of Favorites |

Periphery |

1917 |

21.31 |

41.91 |

95.590 |

.000** |

|

Semi-periphery |

2182 |

43.31 |

70.52 |

|

|

|

|

Core |

2647 |

53.24 |

99.88 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

6746 |

40.96 |

78.68 |

|

|

|

|

Shared Portrayal of

Countries |

Periphery |

1917 |

-50.97 |

160.63 |

107.747 |

.000** |

|

Semi-periphery |

2182 |

-27.76 |

229.15 |

|

|

|

|

Core |

2647 |

38.44 |

239.80 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

6746 |

-8.38 |

219.92 |

|

|

|

**Differences

are significant at .01 level.

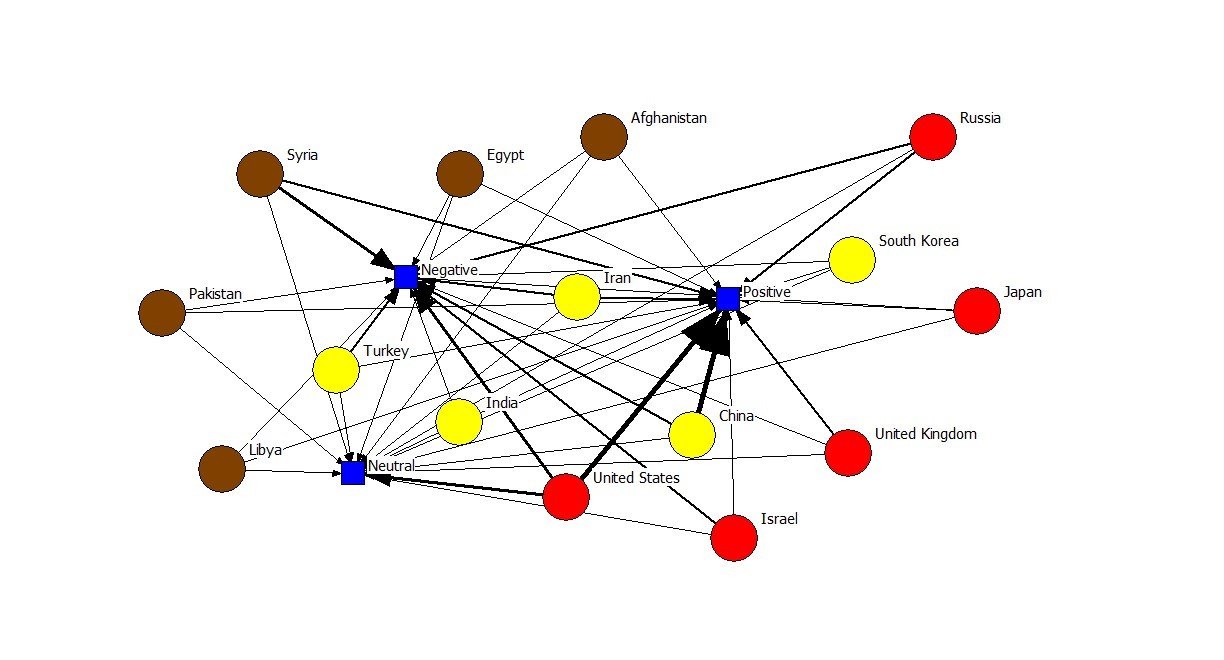

The

shared portrayal is the important variable of this study. Here, it is also

noted that the shared portrayal of periphery and semi-periphery countries is in

a negative direction. On the other hand, it is positive in the case of core

countries (Table 2). Therefore, it provides us with support to confirm H4 that

there are significant differences in the shared portrayal of political news

about the core, periphery and semi-periphery countries. Further, Figure 1

reveals the structure of international coverage of political news about our

sample countries. It shows that core countries are near to the positive

portrayal and their political news are present positively in tweets from

international news agencies. Further, figure 1 indicates that semi-periphery

countries are in the central to positive and neutral direction. They are

presented positively as well as neutrally in political news tweets of

international news agencies. On the other hand, periphery countries are near to

the negative attributes, and they are mostly covered negatively in political news

coverage of international news agencies (Figure 1). Hence, our findings confirm

H4.

Note: Red color denotes core countries, yellow color denotes semi-periphery countries, and brown color denotes periphery countries. Moreover, line thickness shows frequency strength; icons nearness reveals closeness to the portrayal.

Conclusion

The present study found that there are significant differences in the coverage of political news about world countries. Powerful or developed countries are covered more in the tweets of international news agencies. Moreover, these news agencies also portray their soft image in the digital space. The debate doesn’t end here; the study also concludes that Twitter is not bringing any significant change in the landscape of political news flow on the internet. Traditional hierarchies and structures of political news flow still exist on Twitter. Powerful and developed countries are shared more and positively as compared to underdeveloped or developing countries. Therefore, it is concluded that political communication and international communication scholars should work together to formulate the international communication policy based on the principles of free and fair flow of communication in the digital space.

Limitations and Future Research

Due to the time and budget constraints, present study didn’t consider all the world countries for examining their coverage of political news in tweets of international news agencies. Future studies should be conducted with more sample countries. Future research is also needed on other social media platforms, i.e, Facebook, Google News, Instagram, YouTube etc. Research can also be extended to other international media, i.e., BBC News, Voice of America, Al-Jazeera etc.

References

- Alejandro, J. (2010). Journalism in the age of social media. Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper, University of Oxford, 2009-2010.

- Ambrogi-Yanson, M. (2010). International news coverage online as presented by three news agencies. (Masters Unpublished dissertation), Rochester Institute of Technology, New York.

- Anatsui, T. C., & Adekanye, E. A. (2014). Comparative Analysis of Foreign and Local News Agencies: Public Relations Approach in Restoring the Image of the Local Media for National Development. Developing Country Studie, 4(10), 131-142.

- Armstrong, C. L., & Gao, F. (2010). Now tweet this how news organizations use twitter. Electronic News, 4(4), 218-235.

- Atabek, N. (1996). The International news agencies and the new world information order. March 2, 2018, https://earsiv.anadolu.edu.tr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11421/1410/114130.pdf?sequence=1

- Atabek, N. (1996). The International news agencies and the new world information order. March 2, 2018, https://earsiv.anadolu.edu.tr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11421/1410/114130.pdf?sequence=1

- Babones, S. (2005). The country-level income structure of the world-economy. Journal of World- Systems Research, 11(1), 29-55.

- Baum, M. A., & Zhukov, Y. M. (2019). Media ownership and news coverage of international conflict. Political Communication, 36(1), 36-63.

- Bielsa, E. (2008). The pivotal role of news agencies in the context of globalization: a historical approach. Global Networks, 8(3), 347-366.

- Blondheim, M., Segev, E., & Cabrera, M.-ÃÂ. (2015). The prominence of weak economies: Factors and trends in global news coverage of economic crisis, 2009-2012. International Journal of Communication, 9, 46-65.

- Boyd-Barrett, O. (2008). News agency majors: Ownership, control and influence reevaluated. Journal of Global Mass Communication, 1(1/2), 57-71.

- Bruns, A., & Stieglitz, S. (2012). Quantitative approaches to comparing communication patterns on Twitter. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 30(3-4), 160-185.

- Cha, M., Benevenuto, F., Haddadi, H., & Gummadi, K. (2012). The world of connections and information flow in twitter. Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Part A: Systems and Humans, IEEE Transactions on, 42(4), 991-998.

- Chang, T. K. (1998). All countries not created equal to be news: World system and international communication. Communication Research, 25(5), 528-563.

- Chase-Dunn, C., Kawano, Y., & Brewer, B. D. (2000). Trade globalization since 1795: Waves of integration in the world-system. American Sociological Review, 65(1), 77-95.

- Corduneanu-Huci, C., & Hamilton, A. (2018). Selective control: the political economy of censorship: The World Bank.

- Dergisi, K. (1996). The International News Ageneies and the New World Information Order. June 6, 2016, http://dergipark.ulakbim.gov.tr/kurgu/article/viewFile/5000174901/5000157773

- Dergisi, K. (1996). The International News Ageneies and the New World Information Order. June 6, 2016, http://dergipark.ulakbim.gov.tr/kurgu/article/viewFile/5000174901/5000157773

- el-Ojeili, C. (2015). Reflections on Wallerstein: The Modern World-System, Four Decades on. Critical Sociology, 41(4-5), 679-700.

- Giffard, C. A., & Rivenburgh, N. K. (2000). News agencies, national images, and global media events. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 77(1), 8-21.

- Golan, G. J. (2008). Where in the world is Africa? Predicting coverage of Africa by US television networks. International Communication Gazette, 70(1), 41-57.

- Golan, G. J., & Himelboim, L. (2016). Can World System Theory predict news flow on twitter? The case of government-sponsored broadcasting. Information, Communication & Society, 19(8), 1150-1170.

- Griessner, C. (2012). News Agencies and Social Media: a relationship with a future? Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2012-2013.

- Gunaratne, S. A. (2001). Prospects and limitations of world system theory for media analysis: The case of the Middle East and North Africa. Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands), 63(2-3), 121-148.

- Guo, L., & Vargo, C. J. (2017). Global Intermedia Agenda Setting: A Big Data Analysis of International News Flow. Journal of Communication, 67(4), 499-520.

- Hanson, E. C. (1998). The media, foreign policymaking, and political conflict. Mershon International Studies Review, 42(1), 157-163.

- Jirik, J. (2013). The world according to (Thomson) Reuters. Sur le journalisme About journalism Sobre jornalismo, 2(1), pp. 24-41.

- Kick, E. L., McKinney, L. A., McDonald, S., & Jorgenson, A. (2011). A multiple-network analysis of the world system of nations, 1995-1999. In J. Scott & P. J. Carrington (Eds.), Sage handbook of social network analysis (pp. 311-327). London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Koh, H. (2012). A Study on the International News Coverage in the US Media. (Masters Unpublished Dissertation), Michigan State University, USA.

- Kulshmanov, K., & Ishanova, A. (2014). News agencies in the era of globalization and new challenges of reality. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(19), 48-53.

- Letukas, L., & Barnshaw, J. (2008). A world-system approach to post-catastrophe international relief. Social forces, 87(2), 1063-1087.

- Lotan, G., Gaffney, D., & Meyer, C. (2011). Audience analysis of major news accounts on twitter. Social Flow, 3, 211.

- Lotan, G., Graeff, E., Ananny, M., Gaffney, D., & Pearce, I. (2011). The revolutions were tweeted: Information flows during the 2011 Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. International Journal of Communication, 5, 1375-1405.

- Louw, I. P. (2009). The international flow of news regarding the 2003 Irag War: a comparative analysis. (Masters Unpublished Dissertation), University of South Africa, South Africa.

- MacGregor, P. (2013). International news agencies: global eyes that never blink. In K. Fowler- Watt & S. Allan (Eds.), Journalism (pp. 35-63). Bournemouth University, UK: Centre for Journalism & Communication Research.

- Meadow, R. G. (2009). Political violence and the media. Marquette Law Review, 93(1), 231-240.

- Paterson, C. (2003). Prospects for a democratic information society: the news agency stranglehold on global political discourse. Paper presented at the Conference paper, presented to the EMTEL: New Media, Technology and Everyday Life in Europe Conference, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, April.

- Ray, A., & Dutta, A. (2014). Information Imbalance: A Case Study of Print Media in India. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 4(7), 1-5.

- Robinson, W. I. (2007). Theories of Globalization. April, 7, 2016, http://kisi.deu.edu.tr/timucin.yalcinkaya/Theories of Globalization.pdf

- Robinson, W. I. (2007). Theories of Globalization. April, 7, 2016, http://kisi.deu.edu.tr/timucin.yalcinkaya/Theories of Globalization.pdf

- Simon, W. (2011). Centre-Periphery Relationship In Understanding of Development of Internal Colonies. International Journal of Economic Development Research and Investment, 2(1), 147-156.

- Smith, D. A., & White, D. R. (1992). Structure and dynamics of the global economy: network analysis of international trade 1965-1980. Social forces, 70(4), 857-893.

- Sorinel, C. (2010). Immanuel Wallerstein's World System Theory. Annals of Faculty of Economics, 1(2), 220-224.

- Stover, W. A., & Anawalt, H. (1983). Who Makes News? An Inquiry into the Creation and Controls of International Communications. Peace Research, 15(1), 15-23.

- Taylor, P. M. (2003). Global communications, international affairs and the media since 1945. London: Routledge.

- Wallerstein, I. (1974). The modern world system. New York: Academic Press.

- Wallerstein, I. (2004). World-systems analysis: An introduction. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Wanta, W., & Mikusova, S. (2010). The agendasetting process in international news. Central European Journal of Communication, 3(2 (5)), 221-235.

- Wasko, J., Murdock, G., & Sousa, H. (2011). Introduction: the political economy of communications: core, concerns and issues. In J. Wasko, G. Murdock & H. Sousa (Eds.), The Handbook of Political Economy of Communications, (First ed., pp. 1-10). Oxford, London: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Westcott, N. (2008). Digital diplomacy: The impact of the internet on international relations. London: Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

- Willis, A., Fisher, A., & Lvov, I. (2015). Mapping networks of influence: Tracking Twitter conversations through time and space. Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 12(1), 494-530.

- Wu, B., & Shen, H. (2015). Analyzing and predicting news popularity on Twitter. International Journal of Information Management, 35(6), 702-711.

- Wu, H. D. (2000). Systemic determinants of international news coverage: A comparison of 38 countries. Journal of Communication, 50(2), 110-130

- Wu, H. D., Groshek, J., & Elasmar, M. G. (2016). Which Countries Does the World Talk About? An Examination of Factors that Shape Country Presence on Twitter. International Journal of Communication, 10, 1860-1877.

- Wu, S., Hofman, J. M., Mason, W. A., & Watts, D. J. (2011). Who says what to whom on twitter. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 20th international conference on World wide web, Hyderabad, India.

- Yao, F., Chang, K. C. C., & Campbell, R. H. (2015). Ushio: Analyzing News Media and Public Trends in Twitter. IEEE/ACM 8th International Conference on Utility and Cloud Computing (UCC), 424-429.

- Alejandro, J. (2010). Journalism in the age of social media. Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper, University of Oxford, 2009-2010.

- Ambrogi-Yanson, M. (2010). International news coverage online as presented by three news agencies. (Masters Unpublished dissertation), Rochester Institute of Technology, New York.

- Anatsui, T. C., & Adekanye, E. A. (2014). Comparative Analysis of Foreign and Local News Agencies: Public Relations Approach in Restoring the Image of the Local Media for National Development. Developing Country Studie, 4(10), 131-142.

- Armstrong, C. L., & Gao, F. (2010). Now tweet this how news organizations use twitter. Electronic News, 4(4), 218-235.

- Atabek, N. (1996). The International news agencies and the new world information order. March 2, 2018, https://earsiv.anadolu.edu.tr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11421/1410/114130.pdf?sequence=1

- Atabek, N. (1996). The International news agencies and the new world information order. March 2, 2018, https://earsiv.anadolu.edu.tr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11421/1410/114130.pdf?sequence=1

- Babones, S. (2005). The country-level income structure of the world-economy. Journal of World- Systems Research, 11(1), 29-55.

- Baum, M. A., & Zhukov, Y. M. (2019). Media ownership and news coverage of international conflict. Political Communication, 36(1), 36-63.

- Bielsa, E. (2008). The pivotal role of news agencies in the context of globalization: a historical approach. Global Networks, 8(3), 347-366.

- Blondheim, M., Segev, E., & Cabrera, M.-ÃÂ. (2015). The prominence of weak economies: Factors and trends in global news coverage of economic crisis, 2009-2012. International Journal of Communication, 9, 46-65.

- Boyd-Barrett, O. (2008). News agency majors: Ownership, control and influence reevaluated. Journal of Global Mass Communication, 1(1/2), 57-71.

- Bruns, A., & Stieglitz, S. (2012). Quantitative approaches to comparing communication patterns on Twitter. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 30(3-4), 160-185.

- Cha, M., Benevenuto, F., Haddadi, H., & Gummadi, K. (2012). The world of connections and information flow in twitter. Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Part A: Systems and Humans, IEEE Transactions on, 42(4), 991-998.

- Chang, T. K. (1998). All countries not created equal to be news: World system and international communication. Communication Research, 25(5), 528-563.

- Chase-Dunn, C., Kawano, Y., & Brewer, B. D. (2000). Trade globalization since 1795: Waves of integration in the world-system. American Sociological Review, 65(1), 77-95.

- Corduneanu-Huci, C., & Hamilton, A. (2018). Selective control: the political economy of censorship: The World Bank.

- Dergisi, K. (1996). The International News Ageneies and the New World Information Order. June 6, 2016, http://dergipark.ulakbim.gov.tr/kurgu/article/viewFile/5000174901/5000157773

- Dergisi, K. (1996). The International News Ageneies and the New World Information Order. June 6, 2016, http://dergipark.ulakbim.gov.tr/kurgu/article/viewFile/5000174901/5000157773

- el-Ojeili, C. (2015). Reflections on Wallerstein: The Modern World-System, Four Decades on. Critical Sociology, 41(4-5), 679-700.

- Giffard, C. A., & Rivenburgh, N. K. (2000). News agencies, national images, and global media events. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 77(1), 8-21.

- Golan, G. J. (2008). Where in the world is Africa? Predicting coverage of Africa by US television networks. International Communication Gazette, 70(1), 41-57.

- Golan, G. J., & Himelboim, L. (2016). Can World System Theory predict news flow on twitter? The case of government-sponsored broadcasting. Information, Communication & Society, 19(8), 1150-1170.

- Griessner, C. (2012). News Agencies and Social Media: a relationship with a future? Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2012-2013.

- Gunaratne, S. A. (2001). Prospects and limitations of world system theory for media analysis: The case of the Middle East and North Africa. Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands), 63(2-3), 121-148.

- Guo, L., & Vargo, C. J. (2017). Global Intermedia Agenda Setting: A Big Data Analysis of International News Flow. Journal of Communication, 67(4), 499-520.

- Hanson, E. C. (1998). The media, foreign policymaking, and political conflict. Mershon International Studies Review, 42(1), 157-163.

- Jirik, J. (2013). The world according to (Thomson) Reuters. Sur le journalisme About journalism Sobre jornalismo, 2(1), pp. 24-41.

- Kick, E. L., McKinney, L. A., McDonald, S., & Jorgenson, A. (2011). A multiple-network analysis of the world system of nations, 1995-1999. In J. Scott & P. J. Carrington (Eds.), Sage handbook of social network analysis (pp. 311-327). London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Koh, H. (2012). A Study on the International News Coverage in the US Media. (Masters Unpublished Dissertation), Michigan State University, USA.

- Kulshmanov, K., & Ishanova, A. (2014). News agencies in the era of globalization and new challenges of reality. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(19), 48-53.

- Letukas, L., & Barnshaw, J. (2008). A world-system approach to post-catastrophe international relief. Social forces, 87(2), 1063-1087.

- Lotan, G., Gaffney, D., & Meyer, C. (2011). Audience analysis of major news accounts on twitter. Social Flow, 3, 211.

- Lotan, G., Graeff, E., Ananny, M., Gaffney, D., & Pearce, I. (2011). The revolutions were tweeted: Information flows during the 2011 Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. International Journal of Communication, 5, 1375-1405.

- Louw, I. P. (2009). The international flow of news regarding the 2003 Irag War: a comparative analysis. (Masters Unpublished Dissertation), University of South Africa, South Africa.

- MacGregor, P. (2013). International news agencies: global eyes that never blink. In K. Fowler- Watt & S. Allan (Eds.), Journalism (pp. 35-63). Bournemouth University, UK: Centre for Journalism & Communication Research.

- Meadow, R. G. (2009). Political violence and the media. Marquette Law Review, 93(1), 231-240.

- Paterson, C. (2003). Prospects for a democratic information society: the news agency stranglehold on global political discourse. Paper presented at the Conference paper, presented to the EMTEL: New Media, Technology and Everyday Life in Europe Conference, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, April.

- Ray, A., & Dutta, A. (2014). Information Imbalance: A Case Study of Print Media in India. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 4(7), 1-5.

- Robinson, W. I. (2007). Theories of Globalization. April, 7, 2016, http://kisi.deu.edu.tr/timucin.yalcinkaya/Theories of Globalization.pdf

- Robinson, W. I. (2007). Theories of Globalization. April, 7, 2016, http://kisi.deu.edu.tr/timucin.yalcinkaya/Theories of Globalization.pdf

- Simon, W. (2011). Centre-Periphery Relationship In Understanding of Development of Internal Colonies. International Journal of Economic Development Research and Investment, 2(1), 147-156.

- Smith, D. A., & White, D. R. (1992). Structure and dynamics of the global economy: network analysis of international trade 1965-1980. Social forces, 70(4), 857-893.

- Sorinel, C. (2010). Immanuel Wallerstein's World System Theory. Annals of Faculty of Economics, 1(2), 220-224.

- Stover, W. A., & Anawalt, H. (1983). Who Makes News? An Inquiry into the Creation and Controls of International Communications. Peace Research, 15(1), 15-23.

- Taylor, P. M. (2003). Global communications, international affairs and the media since 1945. London: Routledge.

- Wallerstein, I. (1974). The modern world system. New York: Academic Press.

- Wallerstein, I. (2004). World-systems analysis: An introduction. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Wanta, W., & Mikusova, S. (2010). The agendasetting process in international news. Central European Journal of Communication, 3(2 (5)), 221-235.

- Wasko, J., Murdock, G., & Sousa, H. (2011). Introduction: the political economy of communications: core, concerns and issues. In J. Wasko, G. Murdock & H. Sousa (Eds.), The Handbook of Political Economy of Communications, (First ed., pp. 1-10). Oxford, London: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Westcott, N. (2008). Digital diplomacy: The impact of the internet on international relations. London: Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

- Willis, A., Fisher, A., & Lvov, I. (2015). Mapping networks of influence: Tracking Twitter conversations through time and space. Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 12(1), 494-530.

- Wu, B., & Shen, H. (2015). Analyzing and predicting news popularity on Twitter. International Journal of Information Management, 35(6), 702-711.

- Wu, H. D. (2000). Systemic determinants of international news coverage: A comparison of 38 countries. Journal of Communication, 50(2), 110-130

- Wu, H. D., Groshek, J., & Elasmar, M. G. (2016). Which Countries Does the World Talk About? An Examination of Factors that Shape Country Presence on Twitter. International Journal of Communication, 10, 1860-1877.

- Wu, S., Hofman, J. M., Mason, W. A., & Watts, D. J. (2011). Who says what to whom on twitter. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 20th international conference on World wide web, Hyderabad, India.

- Yao, F., Chang, K. C. C., & Campbell, R. H. (2015). Ushio: Analyzing News Media and Public Trends in Twitter. IEEE/ACM 8th International Conference on Utility and Cloud Computing (UCC), 424-429.

Cite this article

-

APA : Saeed, M. U., Shah, M. H., & Ahmad, R. W. (2021). Coverage of Political News in Tweets of International News Agencies: A Comparative Analysis of World-Systems Countries. Global Mass Communication Review, VI(I), 57-69. https://doi.org/10.31703/gmcr.2021(VI-I).05

-

CHICAGO : Saeed, Muhammad Usman, Mudassar Hussain Shah, and Raza Waqas Ahmad. 2021. "Coverage of Political News in Tweets of International News Agencies: A Comparative Analysis of World-Systems Countries." Global Mass Communication Review, VI (I): 57-69 doi: 10.31703/gmcr.2021(VI-I).05

-

HARVARD : SAEED, M. U., SHAH, M. H. & AHMAD, R. W. 2021. Coverage of Political News in Tweets of International News Agencies: A Comparative Analysis of World-Systems Countries. Global Mass Communication Review, VI, 57-69.

-

MHRA : Saeed, Muhammad Usman, Mudassar Hussain Shah, and Raza Waqas Ahmad. 2021. "Coverage of Political News in Tweets of International News Agencies: A Comparative Analysis of World-Systems Countries." Global Mass Communication Review, VI: 57-69

-

MLA : Saeed, Muhammad Usman, Mudassar Hussain Shah, and Raza Waqas Ahmad. "Coverage of Political News in Tweets of International News Agencies: A Comparative Analysis of World-Systems Countries." Global Mass Communication Review, VI.I (2021): 57-69 Print.

-

OXFORD : Saeed, Muhammad Usman, Shah, Mudassar Hussain, and Ahmad, Raza Waqas (2021), "Coverage of Political News in Tweets of International News Agencies: A Comparative Analysis of World-Systems Countries", Global Mass Communication Review, VI (I), 57-69

-

TURABIAN : Saeed, Muhammad Usman, Mudassar Hussain Shah, and Raza Waqas Ahmad. "Coverage of Political News in Tweets of International News Agencies: A Comparative Analysis of World-Systems Countries." Global Mass Communication Review VI, no. I (2021): 57-69. https://doi.org/10.31703/gmcr.2021(VI-I).05